After researching this Guardian article about school exclusions, I discovered the facts used are wrong.

Digging a little deeper, lots of people use the same fake facts.

It turns out, that school exclusions are a hot topic among educators.

And for good reason!

But the discussion is getting unnecessarily messy.

As an educational science researcher, I wanted to understand more.

This article will explore:

- The confusion behind school exclusions.

- Exclusion data and related fake facts.

- School exclusion relations to school behaviour policies.

Where the exclusion confusion begins

Recent confusion about exclusions could be due to renaming from the UK government in 2022.

Temporary or fixed-period exclusions are now suspensions.

Headteachers exclude or suspend students who breach the school’s behaviour policy.

However, schools could internally exclude or isolate a student. Students are sent to rooms away from the mainstream class such as an isolation room.

Each option is a different way to try and encourage good behaviour by students in school.

But issues can arise when people suggest we should focus our efforts on lowering exclusions rates in schools.

What does exclusion refer to?

- Suspensions. Previously known as temporary or fixed-term exclusions.

- Internal exclusions. Often known as being sent to isolation.

- Permanent exclusions. Told to find another educational facility.

Stopping exclusions is not accurate or useful

The title of the mentioned Guardian article reads (as I write this):

'Parents didn't want their kids to be here': inside the troubled London school that stopped excluding pupils and restored calm

‘Stopped excluding pupils’ is a bold, and inaccurate claim.

Going from 300 suspensions to 25 suspensions in 5 years suggests exclusions in this article are meant as permanent exclusions.

But the mentioned school had 2 permanent exclusions in 2021/22 according to the latest data.

2 permanent exclusions doesn't mean stopped.

That drop in suspensions sounds good. Until you look at the drop in headcount.

819 to 381 if you look at 2022/23 data.

This suggests the 275 drop in suspensions means less than what happened to the rate of suspensions.

Data showing a drop from 39.49 in 2017/18 to 14.49 in 2021/22 is good.

But still above the national average suspension rate of 6.91.

However, the average suspension rate can be interpreted in various ways, so I would encourage you to look at the suspension data.

The below image shows a positive trend of declining suspensions and exclusions.

But declining doesn’t mean stopped.

If you look at the government guidance it says:

Schools and local authorities should not adopt a ‘no exclusion’ policy as an end in itself.

Wanting exclusion numbers to drop isn't necessarily the same as wanting improved behaviour in school.

Exclusion data manipulation

The London’s Violence Reduction Unit (VRU) tries to prevent and intervene early to reduce violent behaviour.

A great goal!

Understandably this involves schools. Early intervention.

Schools with higher suspension and exclusion numbers and rates are therefore brought into focus.

The VRU posted an inclusion charter which aims to keep kids in school.

However, two key ‘facts’ used to support ideas about stopping exclusions, are inaccurate:

- Almost one in every two people in prison were excluded as children.

- Kids excluded from school are twice as likely to carry a knife.

Correlation between prison and exclusions

The inclusion charter references a report which says:

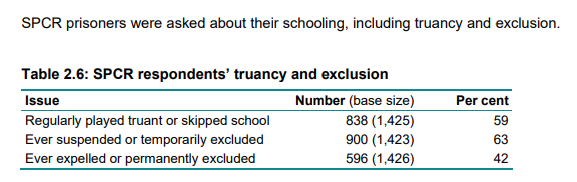

The majority of UK prisoners were excluded from school. A longitudinal study of prisoners found that 63 per cent of prisoners reported being temporarily excluded when at school (MoJ 2012). Forty-two per cent had been permanently excluded, and these excluded prisoners were more likely to be repeat offenders than other prisoners (ibid).

Temporary exclusions are now suspensions so using 63% would be very misleading.

42% is almost one in every two but this data is from a 2012 report.

The 2012 Ministry of Justice report shows that 42% of newly sentenced prisoners from 2005/06 were ever expelled or permanently excluded.

In addition to the data being almost 20 years old, it is survey data from 1 month to four years of newly sentenced prisoners.

Poor memory. Lying. Confusion between exclusion and suspension.

All reasons to doubt the reliability of this data.

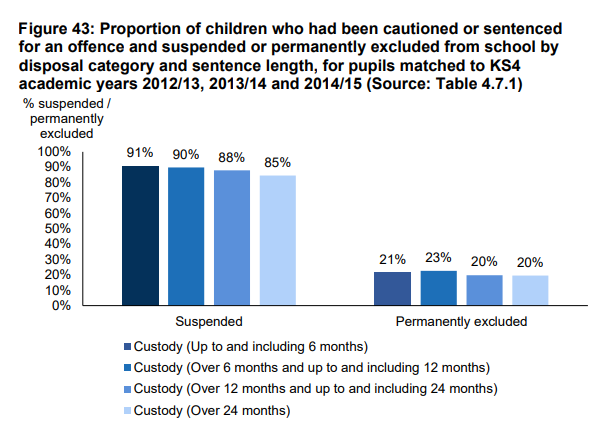

Looking at data from 2022 young offenders. Yes, the sample group is limited but for a reason, I will share in a bit.

The report says:

Overall, 10% of children who had been cautioned or sentenced for an offence had been permanently excluded, compared with 15% of children who had been cautioned or sentenced for a serious violence offence.

So exclusion and violence, violence being VRU’s focus, seem less common than suggested.

When including other offences.

Around 20% of prisoners were permanently excluded. That’s not almost one in every two.

Those wondering about the adult numbers. They aren’t as relevant.

The Department of Education and Ministry of Justice report from 2022 said:

Although there is a relationship between being permanently excluded and being cautioned or sentenced for a serious violence offence, there is often a significant time lag between those two events.

Correlation, not causation.

Despite the correlation, permanent exclusion doesn’t seem to cause violent or criminal behaviour.

This prison 'fact' is at best misleading. At worst. Fake.

Correlation between knife crime and exclusions

The aforementioned inclusion charter says:

An Ofsted report on knife crime showed that children excluded from school are twice as likely to carry a knife

But the referenced report doesn’t say that.

It mentions that “pupils who self-report as being a victim of knife crime are twice as likely to carry a knife themselves compared with non-victims.”

But being a victim of knife crime isn’t the same as being excluded.

It also mentions “PRU attendees, 47% (92 of 196) say they know someone who has carried a knife with them, compared with 25% of non-PRU attendees (1188 of 4673)”.

But attending a PRU (Pupil referral unit) isn’t being out of school.

Going to a PRU isn’t the same as being excluded.

Not all students in PRUs are excluded.

Not all students are there for poor behaviour.

But it is where many students displaying violent or criminal behaviour go, so you would expect the numbers to be high.

Unless I am missing something from the report, the ‘fact’ is NOT supported.

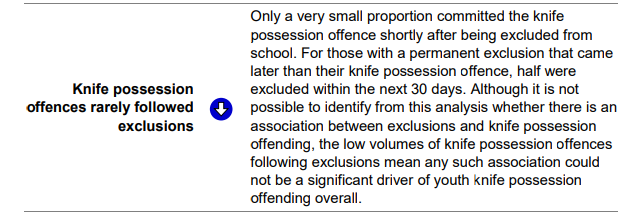

Looking at a Ministry of Justice 2018 report.

Knife offences rarely followed exclusions, doesn’t support ‘Kids excluded from school are twice as likely to carry a knife’.

If anything, this report suggests the opposite.

This knife 'fact' is at best a misunderstanding. At worst. Fake.

Opinions on exclusions and behaviour in school

Inaccurate ‘facts’ can be dangerous.

This Guardian article uses both aforementioned ‘facts’ to support a less punitive behaviour policy.

But educators, policymakers and leaders all have their own opinions.

Like with most decisions, there are 2 ends of a spectrum.

Tough to soft discipline.

More to less punitive.

A spectrum with no right answer.

Using claimed ‘facts’ can persuade opinion. Move people along the spectrum.

This Guardian article uses a quote:

If they just kick you out of school, people carry on misbehaving. But here they give people a chance to fix their ways.

However, I don’t think stopping exclusions is the solution to better behaviour.

As Tom suggests:

The way to reduce exclusions is by reducing the need to exclude, not by simply turning the tap off.

Towards the start I said “wanting exclusion numbers to drop isn’t necessarily the same as wanting improved behaviour in school.”

Tough or soft discipline. More or less punitive.

What matters is better behaviour.

Exclusions help encourage better behaviour. Stopping them seems counter-productive within school behaviour policy.

But unfortunately, these discussions can get unnecessarily personal.

Accusations during discussions

Some accusations are made in discussions about behaviour policy in the Guardian article.

The accusation prefaced with:

The attempt to drive down exclusions has some fierce detractors. They include the government’s own behaviour tsar for England, Tom Bennett, a vocal supporter of tough discipline and silent corridors.

Which doesn’t sound too bad, but sets up this quote:

He describes Bennett’s comments as “the sort of unevidenced thing you hear from people who haven’t actually spent time teaching in schools".

But without discussing specifics, these comments can be dangerous for careers.

It also detracts from how exclusions go down, and what tough discipline means.

Tom did respond to the ‘unevidenced’ accusation by saying he’s:

worked in tough inner city schools in London for over a decade. I’ve visited 950+ schools. I’m a Professor in School Behaviour, written four books on behaviour, and lead national programs of school improvement in school culture. None of which means I am right, but I think I’ve earned the right to claim some level of expertise.

Discussions moving away from the data about exclusions, the facts about crime, the application of policies. Should refocus their attention.

Behaviour in schools is a huge area for discussion.

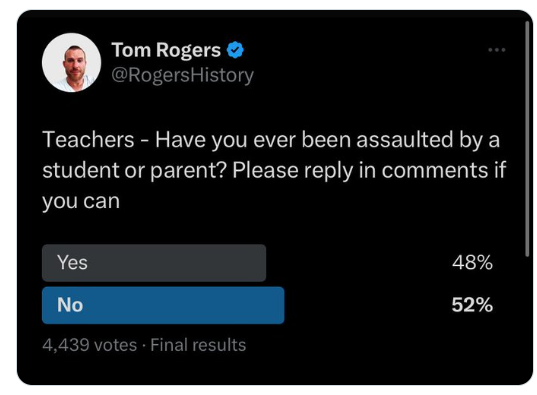

And an important one with the high reported levels of teacher assault.

Exclusion guidance is messy because opinions on behaviour policies differ.

But suggesting we should stop exclusions creates a larger unnecessary mess, fracturing attention and energy.

Recently on X (formally Twitter) I responded to a post about suspensions.

As you can see, I got more likes than the original post.

Granted this is social media with various biases and likes aren’t empirical data.

But exclusion and suspension research doesn’t seem to focus on what educators want.

We should be discussing how we improve behaviour. Not how to reduce exclusions.